How organisations can adopt design & digital - making it happen and dealing with cultural challenges

My colleague Hannah and I recently gave a talk, as part of Digital Leaders Innovation week, about why it’s so beneficial to adopt a design approach for public services; some of the common issues faced by teams and Leaders of legacy systems trying to make the change, and ideas on how to manage them. It’s something I am really passionate about unlocking. So many good teams spend more time dealing with obstacles than they do making a change. We completely understand that every organisation is different, but we do see patterns in the challenges people face – and we hope this might help a little, even if it it’s just cathartic to hear ‘it’s not just here’.

What do we mean by digital?

- Before we start, I am stealing the definition of digital, as a reference point, from Tom Loosemore. It’s a way of tackling challenges, using the methodologies and approaches from the internet age – in particular iterative delivery and user, or human centred design. It’s much more than just about the technology.

Why is Design important?

- Public services have so many challenges at the moment, not just financial, whilst the need for support for residents, businesses, and organisations continue to grow.

- Services that aren’t ‘designed’ tend to just ‘evolve’ with pieces added in ad-hoc. They are often measured against specific component KPIs and not achieving an overall outcome for a citizen or a business. As additional needs arise, or new ways of delivering solutions appear, things get ‘added’ to the service – rather than looking at the end-to-end design again.

The benefits of a human centered design approach

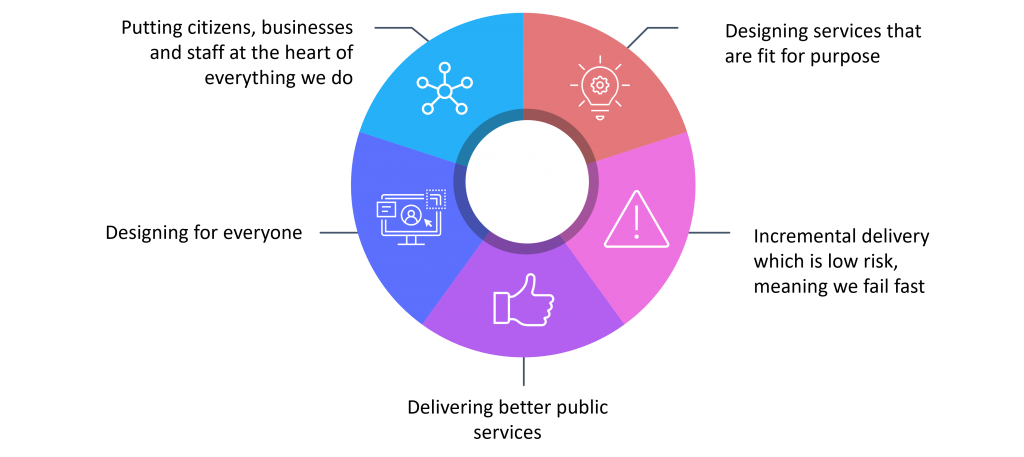

Human centred design is a problem solving approach that puts citizens, staff, businesses, users at the heart of the process to design and deliver a product or service, and can also be applied in an organisation and systems design context.

In practice it means:

- Designing services that are fit for purpose, services that are based on user needs and actually work well

- Designing for everyone: ensuring what we design is accessible and inclusive to everyone

- In a government context, where budgets are tight and teams are stretched, human centred design often goes hand in hand with agile delivery. This means incremental delivery which is low risk, meaning we fail fast

Ultimately government bodies exist to serve citizens, they have a responsibility to deliver really good public services and they should be leading the way in terms of accessibility and inclusion.

Making the change

- We know from listening to, and working alongside people in public authorities, there are loads of great people actively working to make a change in how to design and deliver public services, and they are starting to make this change – but for many – more time is spent manoeuvring and dealing with blockers than is channelled into improving services.

- I think a fundamental reason it can seem so hard is that when first mentioned, it’s treated as just another project delivery model – different documents etc – but nothing else is changed. And that’s the issue.

- This isn’t about just a change of delivery model for a ‘project’. It’s a different way of working, that touches all parts of the organisation, its culture, governance, processes, and structure

- To do it successfully, you need to look at all these things. You can’t lift and shift from running technology project to agile design and delivery.

- We‘ve seen a number of common patterns of the challenges, and ideas on how to manage this, to open the door for human centred design.

Leadership

Before you can even start, there needs to be buy-in from the top, that this is the right approach to take. We spoke earlier on why we think a HCD and a digital approach is crucial to public services, but from experience that isn’t a view widely held, or even understood. I often wonder, if we did a survey of what this concept meant to leaders, would there be many different answers? There are obviously 2 large groups of leadership in authorities – To begin the journey, we need to Win hearts and minds of both:

- Bringing senior leadership onboard – showing compelling examples from elsewhere to gain trust and buy-in

- Building senior leadership understanding and bringing them along the journey

- Looking at measuring organisational performance against outcomes achieved for citizens. We can unintentionally obscure the difficulties for citizens and businesses by focusing on very granular KPIs, such as times taken to answer a call. This is still important, but if that call shouldn’t be needed in the first place, we need to understand that too.

There are lots of brilliant examples of great leadership teams moving forward with a digital approach. We can no longer afford to have leaders who “don’t do digital”. Hearing from peers, has been a great way of sharing learning; and starting simple – showing leaders that they are already using digital tools – online banking, ordering shopping online, social media. It’s about making it easy for leaders to better understand key concepts, and importantly, making it safe for them to ask questions. We expect leaders to have answers, we need to give them a safe space to ask questions too.

Ownership and Silos

We think of digital transformation as being something that sits with and is owned by IT and Digital teams. It often starts there, but it will inevitably have a significant impact on the whole organisation, so bringing in colleagues in wider, key areas is crucial to building momentum and making the change stick.

Public Services aren’t typically set up to think about delivering end-to-end services. Different operational leaders are responsible for different bits of the user journey – one team runs the website, another team runs the call centre, someone else manages front line staff and so forth. This makes it really difficult to assign accountability. We need to be able to step back and look at the big picture and see the whole service as one interconnected thing with lots of different touch points for citizens, businesses, and staff.

- Current management structures don’t always make accountability for end-to-end outcomes easy to assign – different operational leaders are often responsible for different ‘sections’ of the journey, for example comms runs the website, someone else runs the call centre, someone else manages fieldworkers, someone else manages relations with other agencies needed to achieve the outcome.

- Who is leading the way? Who would be accountable in a HCD approach? How do we breakdown the silos to solve the problem?

- Who is going to make a start? Often the HCD approach is being adopted by digital teams – business areas are not used to digital and tech leading on the design of their services – and this often causes tension.

End to End Services

When we talk about design – what are we designing? What is the ‘Service’ we are talking about? There has been a lot of helpful discussion on how a Service is defined in central Government – in essence as something that helps a citizen achieve an outcome.

Some of this translates well to local public services, for example ‘help me pay my council tax’. It’s short, it’s transactional. But a lot of what local authorities do, in partnership with others, is much more complex, ‘keep me and my family together in a safe home’. Mapping these outcomes, how they can be achieved, and how we can measure – is not an easy undertaking. Local Authorities often have a different relationship with their residents and businesses, it’s more personal – less transactional. But it’s still a service.

Governance

This is, to many trying to make a change, one of the most fundamental and frustrating barriers, and it’s certainly not just a barrier for Public Services. Current funding and governance models are not an easy fit with an iterative, agile approach. You need to be able to move quickly through Discovery, Alpha through to iterative delivery in Beta, and this doesn’t fit with drawn-out approval cycles.

Then there is the structure of a business case. It’s still generally far easier to get sign off for some off-the-shelf product with a definite price, even if it doesn’t meet all the user needs, and is not based on user research, than it is to get funding for a Discovery and Alpha. This is where ‘digital’ is seen as a product to buy, not ‘how we work now’.

I completely understand why, when faced with rising debts and lower income, there is little appetite to take what is seen as a ‘risk’. But is this the risk? If we are really focused on achieving outcomes perhaps buying something that hasn’t been designed and developed around user needs is a much bigger risk than taking the time to understand and design a service around them. Continually managing with aging and siloed technology is not just a risk, it’s a live issue. And not one commonly understood by a bottom-line figure on a business case.

Decision Making

Most decision makers are often instinct led, making decisions based on gut feel, but it’s essential our leaders start to use data and evidence to guide these decisions instead. We need to make it safe for decision makers to go against their instincts and be guided by the evidence, and to start to see data in a holistic way. The only way of holding senior leaders to this is to have them publish the decisions they’ve made, and the evidence used to make them. You can demonstrate this through one directorate to start with to get buy-in and then roll it out more widely. In order to make this happen the data has to be available and easy to access, and then it’s about making it meaningful.

We need to make it ok to bring a data analyst or a user researcher into the room with senior leaders to bring to life what the evidence is telling us. So often the nuance of evidence gets lost in translation between layers of seniority. We shouldn’t expect our senior leaders to be data whizzes, they just need to be comfortable relying on the experts.

We see a lot of staff make the assumption that we already know everything about our service users – and we really don’t. I often see teams relying on a small ‘ panel’ who become expert users in time, and guide a huge number of decisions for the much wider population. Panels do not replace genuine user research with a cross section of users.

Finally, not everything can be a priority, otherwise nothing is, and nothing moves forward at all. You must choose what your priorities are, and there can only be a few.

Buying things

Historically Government has followed the well-trodden path of buying a ‘system’ for an area of the business, and then working business processes and citizen interactions around it. These systems have not always been designed from a human centred design approach. They also tended to be really locked in, preventing data sharing or making changes expensive. Many are written in programming languages that are now generally retired. Tech debt is a big issue. Moving away from this wholesale in one leap is never going to happen. But it needs to be chipped away at. The problem is you can’t afford to do anything new, if all your people are required to continually scoop water out of a sinking ship. It’s a vicious circle.

Capabilities

To do Human Centred Design well, we need to work in multidisciplinary teams with a range of different skill sets, including user researchers, service designers, user experience designers, content designers, product managers, and others. All of these skill sets are currently in short supply, and not easy for teams to hire in-house. Central Government, who have been on this journey longer, have established digital teams and have developed some excellent resources explaining the roles, skills and functions in a team – have a look on gov.uk if you’re interested.

For Public Services such as Education, Local Gov, NonProfit & Travel, growing your own talent, sharing across different organisations, and some ‘rounded people’, are going to be key to make it pragmatically possible. These skills are not generalist, and competitive packages don’t often align to internal grades which are typically based on how many people a role manages.

We need to make job descriptions attractive to people in this industry, they need to be exciting and advertised all over social media. Some organisations hold information evenings for people to drop in and hear more about the roles that are advertised, the culture of the team and types of work that is being done. These are great opportunities to really get people excited about working in the Public Services space. The work done is so important and has a real impact on the lives of citizens – we need to capitalise on this opportunity, because, more than ever before, people care about doing meaningful work. Having said that, drawn out recruitment processes put off prospective candidates, so we need to get faster at hiring.

People in digital and design roles are used to working in environments conducive to agile working, with colleagues who are ‘digital natives’ or something close to that. Hackney did a brilliant job of building its digital team over a few years and that is certainly paying dividends now. One of the things Hackney did was give their team Macs and stickers, as well as appropriate tools for collaborative working – they use Google, not Microsoft. It sends a signal to the team that this is a modern place to work that gives you the right tools to do the job, and it makes digital natives feel at home.

Culture

We’ve talked about skills and governance amongst others, but really, it’s about the culture of an organisation, the environment and ways of working.

Working in the open is a key part of digital delivery – it’s about sharing what you’re doing, inviting discussion along the way and being open to feedback. Sharing should be through weeknotes, show and tells, and putting your project work up on the walls so it’s visible for others to engage with. Being open about what hasn’t worked and mistakes that have been made, and the subsequent learnings are also important in creating safety. We all have successes and failures, and we can all learn from each other’s. Encouraging leaders to be open about their own learnings, and the learning journey they are on, creates psychological safety for everyone and will trickle down to teams on the ground.

In Hackney the team co-designed the HackIT manifesto, which has 11 principles, including things like ‘share don’t send’, ‘accessibility always’, ‘people first’, ‘think big, act small’. The leadership set out that if the team acts in accordance with the manifesto, they will always be supported. The intention was to create a culture of experimentation through psychological safety, where teams were completely trusted.

Working in the open is also about sharing components and research findings. There might be a local bent on what you’re doing, but broadly school transport looks the same whether you’re in Derby or Devon. Given the limited resources in this sector, it makes sense to share good work that is happening with our colleagues in other authorities. We need to recognise where there is commonality, and where we can learn from others, and facilitate that learning, through sharing of resources, contributing to pattern libraries and research repositories.

Collaboration

I truly believe one of the success stories in Public Services is that of collaboration across design and digital teams. But there is potential for so much more. The speed of turnaround and delivery through lockdown was phenomenal. And many achieved that via sharing.

Speaking to the Welsh Local Government Association, their purpose is to facilitate moving councils from a state of competition to collaboration, to mutual support – pushing each other further to be better.

Sharing design patterns, user research libraries, methodologies, perhaps sharing skilled people, sharing code repositories – this is happening at a team level, and it needs to be given real time and focus too. Collaboration, and sharing how problems are being tackled, and cultures re-shaped, is to me the way forward.

Language

In some areas of Public Services, leaders are bridging the gap between the digital people and technology people – using language really carefully to not alienate one from the other, instead using plain English, neutralising terms. This helps to foster a shared sense of purpose, and break down silos.

Where to start?

Making the change

You’ve got to start somewhere – try week notes, do a show and tell

Don’t know everything about our users: Everyone should be exposed to outputs from user research at least every two months

Question how we are measuring success – do our current KPIs tell us how we are serving our residents. Measure against outcomes – not just KPIs

Learn from as many people as possible who are already working in the open – Twitter, events, blogs, podcasts, slack, events.